A thread in a Facebook group I belong to begins with one writer’s most-hated book: The Fountainhead. I immediately feel a chime of agreement. Though I’ve never read The Fountainhead, I did force myself to finish Atlas Shrugged after a friend said it was her favorite book. There’s no way I would subject myself to another Ayn Rand screed posing as a story.

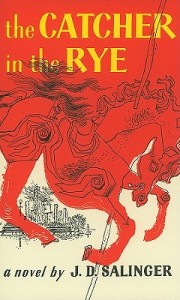

But further down the thread, other members of the group express different ideas. Their most-hated books and authors include some of my favorites: The Princess Bride, by William Goldman; J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books as well as The Casual Vacancy; anything by Barbara Kingsolver; something else by Stephen King. There were also the usual suspects: Hemingway, Faulkner, Austen, and Moby Dick on the “literature” side, Fifty Shades and Twilight among the commercially successful. One that surprised me was how many hate Holden Caulfield.

I didn’t bother to raise my voice in agreement with the Ayn Rand haters, but I read every post until my internet connection clicked off. If anything, it should make writers very, very happy to know that such famous and popular authors are also thoroughly hated by a few. You can’t please everybody, so you might as well write what pleases you. A few rejections might just mean that you haven’t yet reached the readers who love your work.